DEI DELITTI E DELLE PENE (ON CRIMES AND PUNISHMENTS) BY CESARE BECCARIA: A LANDMARK FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF HUMAN CIVILIZATION

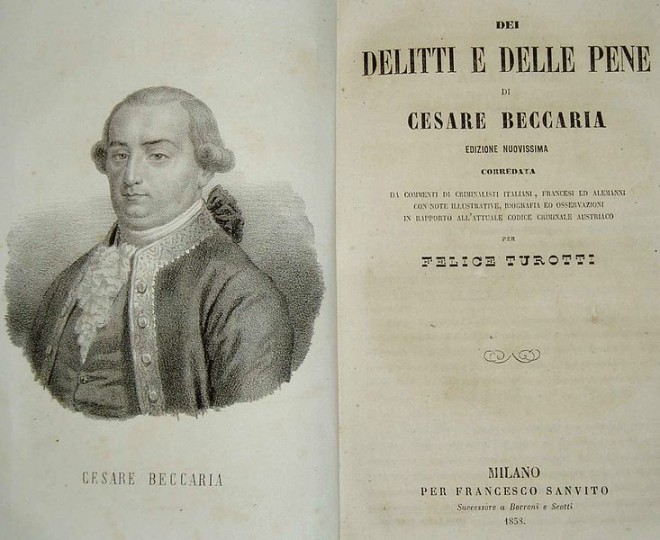

A plain and simple title page, that besides the title itself shows only a small woodcut decoration, a motto from Francis Bacon’s Sermons, and the publication date, distinguishes the extremely rare first edition of Dei delitti e delle pene by Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794), printed anonymously in 1764 by Marco Coltellini in Livorno.

The evolution of this volume must be seen within the intellectual context of the Lombard capital at that time. The young marquis Beccaria - a friend of Pietro and Alessandro Verri, Alfonso Longo, Luigi Lambertenghi and, above all, of the cremonese Giambattista Biffi - frequents the newly founded Accademia dei Pugni (1761), whose members used to meet at Pietro Verri’s house, in the district of Monte di Santa Teresa (now called Via Montenapoleone), to discuss matters concerning the Enlightenment, economics and finance, which were very popular issues in Milan towards the end of the Seven Years’ War. Cesare Beccaria himself stated that “his ‘conversion to philosophy’ dated back to 1761 and had initially been sponsored by Montesquieu’s Lettres persanes (Persian Letters) […]. Buffon, Diderot, Hume, d’Alembert, Condillac were the following steps of Beccaria’s approach to the ideas of the Enlightenment. It is necessary to add the work, the ideas and the spirit of J.-J. Rousseau, whose deepest appeal, perhaps, ended up covering any other voice in Beccaria’s mind” (DBI 7, 1970).

Dei delitti e delle pene was written in a short time, between March 1763 and January 1764, in the attempt to firmly oppose torture and the death penalty, which used to be inflicted in Milan for about thirty criminal offences, including even theft. The Verri brothers provided the decisive step for its realisation. Alessandro, who had just graduated in Law, and worked as a “Protector of Prisoners”, shared with the members of the Accademia his daily experience of misery and complaints, of a cruel and arbitrary penal system with its barbarous methods and secret trials. On the other hand, Pietro, who had already been a “Protector of Prisoners”, published his Orazione panegirica sulla giurisprudenza milanese (Panegyrical oration on Milanese jurisprudence) in 1763. He deals with this matter also in the essay Sulla interpretazione delle leggi (On the interpretation of laws), (published in the magazine Il Caffè in 1765) and in Osservazioni sulla tortura (Observations on Torture), (1776-1777).

Within a very short time from its publication, Dei delitti e delle pene was put on the Index of Forbidden Books. The world was not ready yet for the dramatic changes suggested by this volume regarding cruel and useless tortures and death penalty for insubstantial and tenuous crimes. It is no coincidence that the treatise was published in Livorno with its sizeable British colony, in an open context, favourable to the Enlightenment and oriented against restrictions and censorship. However, the small volume, now considered “one of the most influential books in the history of criminology” (Printing and the Mind of Man, number 209), had an immediate success: six editions were published within eighteen month, and it was eventually translated into 22 languages. “Beccaria maintained that the gravity of the crime should be measured by its injury to society and that the penalties should be related to this. The prevention of crime he held to be of greater importance than its punishment, and the certainty of punishment of greater effect than its severity. He denounced the use of torture and secret judicial proceedings. He opposed capital punishment, which should be replaced by life imprisonment; crimes against property should be in the first place punished by fines, political crimes by banishment; and the conditions in prisons should be radically improved […][his] ideas have now become so commonplace that is difficult to appreciate their revolutionary impact at the time” (Printing and the Mind of Man, number 209).

In spite of its popularity, copies of the first edition are not often subject to auctions: An uncut copy without errata leaf - similar to the copy offered by Bolaffi - was sold last time in Italy in 2005 for 11,780 €. Particularly interesting also the fact, that a rare booklet intitled Osservazioni critiche di Callimaco Limi sul libro intitolato Dei delitti e delle pene stampato nel 1764 (Critical remarks by Callimaco Limi on the book entitled On Crimes and Punishments printed in 1764) is bound within the text. Anonymously published, but written by Camillo Almici, Giovanni Maria Mazzucchelli and Giovanni Battista Rodella, the pamphlet edited in tome 13 of the magazine Nuova raccolta d’opuscoli scientifici e filologici (New collection of scientific and philological booklets) in 1765, demonstrates the immediate debate with Beccaria’s text by contemporary authors.

By Annette Popel Pozzo

The evolution of this volume must be seen within the intellectual context of the Lombard capital at that time. The young marquis Beccaria - a friend of Pietro and Alessandro Verri, Alfonso Longo, Luigi Lambertenghi and, above all, of the cremonese Giambattista Biffi - frequents the newly founded Accademia dei Pugni (1761), whose members used to meet at Pietro Verri’s house, in the district of Monte di Santa Teresa (now called Via Montenapoleone), to discuss matters concerning the Enlightenment, economics and finance, which were very popular issues in Milan towards the end of the Seven Years’ War. Cesare Beccaria himself stated that “his ‘conversion to philosophy’ dated back to 1761 and had initially been sponsored by Montesquieu’s Lettres persanes (Persian Letters) […]. Buffon, Diderot, Hume, d’Alembert, Condillac were the following steps of Beccaria’s approach to the ideas of the Enlightenment. It is necessary to add the work, the ideas and the spirit of J.-J. Rousseau, whose deepest appeal, perhaps, ended up covering any other voice in Beccaria’s mind” (DBI 7, 1970).

Dei delitti e delle pene was written in a short time, between March 1763 and January 1764, in the attempt to firmly oppose torture and the death penalty, which used to be inflicted in Milan for about thirty criminal offences, including even theft. The Verri brothers provided the decisive step for its realisation. Alessandro, who had just graduated in Law, and worked as a “Protector of Prisoners”, shared with the members of the Accademia his daily experience of misery and complaints, of a cruel and arbitrary penal system with its barbarous methods and secret trials. On the other hand, Pietro, who had already been a “Protector of Prisoners”, published his Orazione panegirica sulla giurisprudenza milanese (Panegyrical oration on Milanese jurisprudence) in 1763. He deals with this matter also in the essay Sulla interpretazione delle leggi (On the interpretation of laws), (published in the magazine Il Caffè in 1765) and in Osservazioni sulla tortura (Observations on Torture), (1776-1777).

Within a very short time from its publication, Dei delitti e delle pene was put on the Index of Forbidden Books. The world was not ready yet for the dramatic changes suggested by this volume regarding cruel and useless tortures and death penalty for insubstantial and tenuous crimes. It is no coincidence that the treatise was published in Livorno with its sizeable British colony, in an open context, favourable to the Enlightenment and oriented against restrictions and censorship. However, the small volume, now considered “one of the most influential books in the history of criminology” (Printing and the Mind of Man, number 209), had an immediate success: six editions were published within eighteen month, and it was eventually translated into 22 languages. “Beccaria maintained that the gravity of the crime should be measured by its injury to society and that the penalties should be related to this. The prevention of crime he held to be of greater importance than its punishment, and the certainty of punishment of greater effect than its severity. He denounced the use of torture and secret judicial proceedings. He opposed capital punishment, which should be replaced by life imprisonment; crimes against property should be in the first place punished by fines, political crimes by banishment; and the conditions in prisons should be radically improved […][his] ideas have now become so commonplace that is difficult to appreciate their revolutionary impact at the time” (Printing and the Mind of Man, number 209).

In spite of its popularity, copies of the first edition are not often subject to auctions: An uncut copy without errata leaf - similar to the copy offered by Bolaffi - was sold last time in Italy in 2005 for 11,780 €. Particularly interesting also the fact, that a rare booklet intitled Osservazioni critiche di Callimaco Limi sul libro intitolato Dei delitti e delle pene stampato nel 1764 (Critical remarks by Callimaco Limi on the book entitled On Crimes and Punishments printed in 1764) is bound within the text. Anonymously published, but written by Camillo Almici, Giovanni Maria Mazzucchelli and Giovanni Battista Rodella, the pamphlet edited in tome 13 of the magazine Nuova raccolta d’opuscoli scientifici e filologici (New collection of scientific and philological booklets) in 1765, demonstrates the immediate debate with Beccaria’s text by contemporary authors.

By Annette Popel Pozzo