LANDSCAPE IN AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHY

Photography, along with film, has painted a new picture of the American landscape. As far back as the nineteenth-century, photographers like Timothy O’Sullivan and William Henry Jackson captured the United States of America in its birth throws, with images of boundless landscapes. But it was in the twentiethcentury that the American landscape was portrayed in all its eloquent glory, with breath-taking panoramas second to none.

Going against the popular trend in pictorial art during the early twentieth-century, some photographers broke out of the mould that favoured soft tones and pastel shades, a style hailing to that of consolidated pictorial art. A few of these photographers set up Group f/64 in 1932. The name says it all: f/64 refers to the minimum aperture of the diaphragm used to take pictures in which definition and detail of the image are salient qualities.

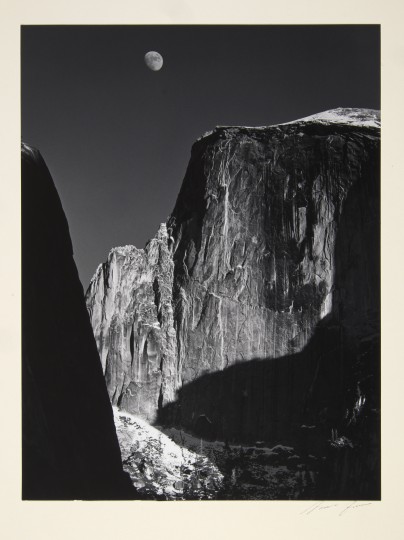

One of the founding members of the group, Ansel Adams was certainly one of the photographers who revitalized the concept of landscape photography, paving the way for photographers of the modern age. For Adams, nature was no longer enveloped in a romantic, nebulous atmosphere. The grandeur and sharpness of the pictures portray the absolute beauty of the subject, without any interference from man. Adams captures the dramatic thrill of landscapes with the contrast between light and dark that emphasise the quality of the rock. The sophisticated images, printed with almost maniac attention to detail, give a sense of detail to the subject that’s all but palpable. One fine example of this purity in rendering the spirit of a landscape is Moon and Half Dome, one of his most famous photographs. Newhall, in his book mentions: “The photographer, like a musician, knows and controls his instrument to perfection. Nothing is left to chance, and the photographer is free to concentrate on the aesthetic aspects of the composition, knowing full well that the results will be excellent not only in technical terms, but will also portray their own personal interpretation of the subject.”

While Adams concentrates entirely on the contemplation of nature as a wild place, uncontaminated by the presence of man, one of his peers, Berenice Abbott dedicated her efforts to capturing the urban landscape of New York, the big city, with its huge skyscrapers that seem to challenge the very laws of nature.

Abbott moved to Paris in the 20’s and was swept up in the lively cultural world of that time. One of the leading figures of the Dada group introduced her to photography. Man Ray in fact hired her as his darkroom assistant and introduced her to the work of another great French photographer, Eugene Atget. When she returned to the States, Abbott adopted a direct approach to photography, portraying the subject realistically without attempting to manipulate or distort reality. In the picture shown here, New York, Rector Street Italian Festival, Abbott emphasizes the magnificence of the buildings reaching for the sky, blocking out the view, skilfully combining the grey tones of the buildings to create an abstract composition of cubes. The festival in the title, is a mere detail of festooned lights.

Aaron Siskind, just a year older than Ansel Adams, became interested in photography quite late in life, and his pictures were vivid documents denouncing the ills of society. As a member of The Photo League, a cooperative of photographers dedicated to documenting conditions of poverty and inequality, he produced various reportages on social issues. He changed direction in the 50’s when he decided to concentrate on abstract photography. His lens didn’t capture imposing subjects, like the mountains and nature of Adams, or the cities stacked with huge skyscrapers of Abbott, but concentrated on details, often overlooked as insignificant or secondary. The protagonists of Siskind’s photographs are objects that have been abandoned, broken-up paving or peeling walls the photographer immortalizes in his abstract space. Lima 141, a nondescript wall smeared with colour, wasn’t a photo produced by manipulating the image but one captured by the photographer’s eye, framing detail to create a new subject.

The approaches of these men and women to photography differ in terms of subject: nature, the city, detail. But all have one thing in common, portraying the real, concrete image, without resorting to any special effects to manipulate the result. What stands out in these images is the faithful portrayal of the subject using an instrument of purity, a lens that sees clearly without distorting; and by capturing the subject, transforms it into an aesthetic object.

By Silvia Berselli

Going against the popular trend in pictorial art during the early twentieth-century, some photographers broke out of the mould that favoured soft tones and pastel shades, a style hailing to that of consolidated pictorial art. A few of these photographers set up Group f/64 in 1932. The name says it all: f/64 refers to the minimum aperture of the diaphragm used to take pictures in which definition and detail of the image are salient qualities.

One of the founding members of the group, Ansel Adams was certainly one of the photographers who revitalized the concept of landscape photography, paving the way for photographers of the modern age. For Adams, nature was no longer enveloped in a romantic, nebulous atmosphere. The grandeur and sharpness of the pictures portray the absolute beauty of the subject, without any interference from man. Adams captures the dramatic thrill of landscapes with the contrast between light and dark that emphasise the quality of the rock. The sophisticated images, printed with almost maniac attention to detail, give a sense of detail to the subject that’s all but palpable. One fine example of this purity in rendering the spirit of a landscape is Moon and Half Dome, one of his most famous photographs. Newhall, in his book mentions: “The photographer, like a musician, knows and controls his instrument to perfection. Nothing is left to chance, and the photographer is free to concentrate on the aesthetic aspects of the composition, knowing full well that the results will be excellent not only in technical terms, but will also portray their own personal interpretation of the subject.”

While Adams concentrates entirely on the contemplation of nature as a wild place, uncontaminated by the presence of man, one of his peers, Berenice Abbott dedicated her efforts to capturing the urban landscape of New York, the big city, with its huge skyscrapers that seem to challenge the very laws of nature.

Abbott moved to Paris in the 20’s and was swept up in the lively cultural world of that time. One of the leading figures of the Dada group introduced her to photography. Man Ray in fact hired her as his darkroom assistant and introduced her to the work of another great French photographer, Eugene Atget. When she returned to the States, Abbott adopted a direct approach to photography, portraying the subject realistically without attempting to manipulate or distort reality. In the picture shown here, New York, Rector Street Italian Festival, Abbott emphasizes the magnificence of the buildings reaching for the sky, blocking out the view, skilfully combining the grey tones of the buildings to create an abstract composition of cubes. The festival in the title, is a mere detail of festooned lights.

Aaron Siskind, just a year older than Ansel Adams, became interested in photography quite late in life, and his pictures were vivid documents denouncing the ills of society. As a member of The Photo League, a cooperative of photographers dedicated to documenting conditions of poverty and inequality, he produced various reportages on social issues. He changed direction in the 50’s when he decided to concentrate on abstract photography. His lens didn’t capture imposing subjects, like the mountains and nature of Adams, or the cities stacked with huge skyscrapers of Abbott, but concentrated on details, often overlooked as insignificant or secondary. The protagonists of Siskind’s photographs are objects that have been abandoned, broken-up paving or peeling walls the photographer immortalizes in his abstract space. Lima 141, a nondescript wall smeared with colour, wasn’t a photo produced by manipulating the image but one captured by the photographer’s eye, framing detail to create a new subject.

The approaches of these men and women to photography differ in terms of subject: nature, the city, detail. But all have one thing in common, portraying the real, concrete image, without resorting to any special effects to manipulate the result. What stands out in these images is the faithful portrayal of the subject using an instrument of purity, a lens that sees clearly without distorting; and by capturing the subject, transforms it into an aesthetic object.

By Silvia Berselli