A BIT OF EGYPT IN TURIN

“The road to Memphis and Thebes runs through Turin.” Thus declared the Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832), who came to the capital of Piedmont in 1824 to study Bernardino Drovetti’s Egyptian collection. That same notion marked our decision to offer up the editio princeps of I monumenti dell’Egitto e della Nubia (Monuments of Egypt and Nubia) by Ippolito Rosellini (1800- 1843), published in Pisa between 1832 and 1844 and never before seen in an Italian auction until last 30 October. From an outstanding source, the specimen was part of the Duke of Genoa’s library and still bears the coat of arms and royal bookplate. Among the most authoritative and important of its kind in the 1800s, this monumental work by Champollion and Rosellini ushered in scientific interest in Egyptian civilization and exploration in Egypt, a true fever that broke out right after Napoleon’s campaign. The publication consists of nine volumes of text and three large folio volumes of plates. It holds the results of the Franco-Tuscan expedition conceived and led by Champollion, who earned the ever-lasting honor of deciphering hieroglyphics in 1822, thanks to the Rosetta Stone. He was aided by his student and friend Rosellini, an Orientalist from the University of Pisa. Financed by Charles X of France and Leopold II of Lorraine, Grand Duke of Tuscany, the mission undertook an adventurous trip over fifteen months to visit the main Egyptian sites-Giza, Saqqara, Memphis, Beni Hassan, Thebes and Philae-going all the way to Abu Simbel and Wadi Halfa in Nubia.

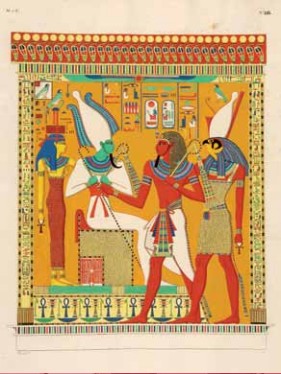

The vividness and accuracy of the observations gathered during the trip are reflected and evidenced in the edition’s rich iconographic illustrations, enhanced by numerous full-page and folding plates. To be exact, there are 12 folding plates and 44 full-page plates in the nine volumes of text, and in the three large folio volumes there are 390 lithographic plates, of which 136 are painted and hand-coloured. The objective was to document ancient Egyptian monuments, still mostly unknown, and to start up a collection of Egyptian artifacts. When the trip concluded, Champollion produced his Notice sommaire sur l’histoire de l’Egypte (Paris, Firmin Didot 1833), while Rosellini published I monumenti dell’Egitto e della Nubia, put up for auction on 30 October in Turin. At the end of the mission, the Italian scholar took back an imposing quantity of material to Tuscany, with more than a thousand Egyptian artifacts (which were to embellish Lorraine’s collections), a similar number of drawings and handwritten notes, a naturalist collection and even a mummy. Their success went well beyond the mere collection of artifacts (what had been done till then), since the copies and survey drawings of monuments they presented in Europe made it possible to begin a philological endeavor to sort out ancient Egyptian history. In fact, Champollion and Rosellini’s expedition was the first with solely scientific intent, and, furthermore, the first example of highly effective international teamwork among scholars.

By Annette Popel Pozzo

The vividness and accuracy of the observations gathered during the trip are reflected and evidenced in the edition’s rich iconographic illustrations, enhanced by numerous full-page and folding plates. To be exact, there are 12 folding plates and 44 full-page plates in the nine volumes of text, and in the three large folio volumes there are 390 lithographic plates, of which 136 are painted and hand-coloured. The objective was to document ancient Egyptian monuments, still mostly unknown, and to start up a collection of Egyptian artifacts. When the trip concluded, Champollion produced his Notice sommaire sur l’histoire de l’Egypte (Paris, Firmin Didot 1833), while Rosellini published I monumenti dell’Egitto e della Nubia, put up for auction on 30 October in Turin. At the end of the mission, the Italian scholar took back an imposing quantity of material to Tuscany, with more than a thousand Egyptian artifacts (which were to embellish Lorraine’s collections), a similar number of drawings and handwritten notes, a naturalist collection and even a mummy. Their success went well beyond the mere collection of artifacts (what had been done till then), since the copies and survey drawings of monuments they presented in Europe made it possible to begin a philological endeavor to sort out ancient Egyptian history. In fact, Champollion and Rosellini’s expedition was the first with solely scientific intent, and, furthermore, the first example of highly effective international teamwork among scholars.

By Annette Popel Pozzo